New Zealand’s high level of car use in our major cities has contributed to urban congestion and a raft of other social, environmental, health and economic impacts. Urban congestion adds costs to doing business, affects productivity and wellbeing of our people.

While efforts to curb carbon emissions(external link) are increasingly supported, debate continues around what actions to take and when. It is clear from the Ministry’s Hīkina te Kohupara(external link) discussion document and the Climate Change Commission’s final advice(external link) that focusing on vehicle and fuel technologies alone is not enough to reduce transport emissions at the scale, and within the timeframe, needed.

Currently, over 85 percent[1] of our population reside in urban areas. Congestion will get worse as the economy continues to grow if the current travel patterns and preference continue. Over-reliance on cars also means considerable effort would be required to decarbonise the vehicle fleet. With vehicle supply and price constraints, we need to reimagine the way we provide access in our cities.

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) could play a key role in achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050. It can help shape urban mobility patterns and demand through better integrating transport, land use and urban development planning.

What is TOD?

TOD is a widely adopted planning strategy that focuses on land use and urban development to facilitate the use of public transport and active modes, and support liveable communities. It requires a coordinated approach to urban design and public transport infrastructure planning to make public transport and active modes more accessible and attractive. This is achieved by encouraging higher densities and mixed land uses around public transport stations and stops. Mixed land use includes both residential and non-residential uses (e.g. providing a range of housing choices, employment and educational opportunities, shops and services, and community facilities).

Why is TOD important?

TOD can help to reduce trip distances and the need to travel by co-locating residential, employment, educational, social and community facilities. Even a small reduction in car travel can result in significant improvements in traffic flow and journey time reliability, thereby improving productivity and economic growth. This would also reduce greenhouse and harmful transport emissions, reduce exposure to road safety risk and improve public health. Reducing the reliance on cars also increases our resilience to natural hazards and events.

Best practice principles to guide TOD planning

A common misunderstanding of TOD is that it solely focuses on increasing population density and constructing more high-rise buildings. In fact, the effects of density alone on increasing the use of public transport and active modes are relatively modest. For example, a 2010 meta-analysis of TOD found the effects from density on reducing car dependency is less than one-quarter of that from improving urban design and half of that from increasing the mix of land uses and activities.

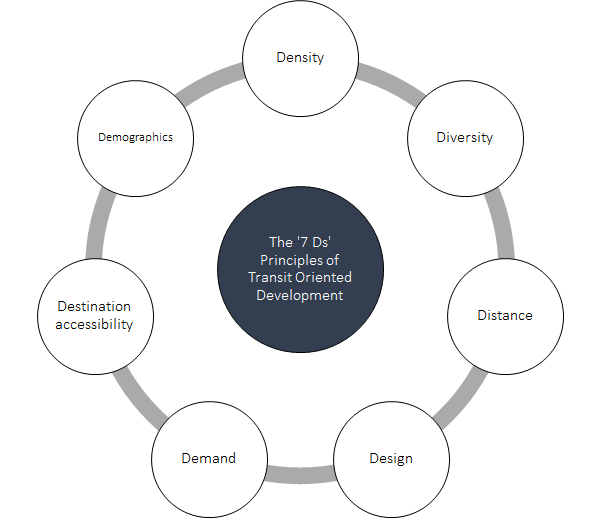

To reduce car dependency through changing the built environment, we need to consider factors other than density. These include: diversity, design, destination accessibility, distance to transit, demand management and demographics. Collectively these are referred as the 7 Ds. They have been used internationally as a set of best practice principles to guide TOD planning (see diagram below). Below provides a quick summary of these overlapping principles.

- Design – Prioritise walking and cycling through effective street and station designs to reduce reliance on car use

- Distance – Co-locate public transport and centre to make public transport the focal point

- Density – Optimise residential and employment densities with higher density within a specific walking distance threshold (e.g. 10-minute walk) and less dense on the periphery to reduce distance of travel

- Diversity – Create complementary mix of land uses and activities within higher density zone to make urban centre a safe and attractive destination to live, work and play

- Destination accessibility – Make public transport options highly accessible, well connected and integrated with surrounding environment to support inclusive access for all ages and abilities

- Demand management – Use complementary measures such as parking measures to manage demand and allow better mode choice decisions

- Demographics – Understand how demographics influence basic, social and economic needs and their associate behavioural changes

Making better use of TOD

Work has already commenced in New Zealand to overcome the common barriers of TOD so we can take advantage of the benefits it offers.

To be successful in TOD, consistency of policy and investment planning process and improvement in the coordination across actors involved in land use, urban development and transport planning are important. We are already seeing increasing efforts being invested on this such as the establishment of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development and the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission to facilitate greater coordination across sectors and agencies; staff on rotation or secondment between institutions for the reform of the Resource Management Act; elaboration of regional plans and policy to include greater land use and transport planning to ensure governance continuity.

We need to manage the potential impact of TODs on affordable housing (e.g. gentrification). Strategies could, and some are already being considered, include ensuring that there is a range of housing choices available; planning and investing in public housing as part of TODs; improving connections to communities further away from public transport hubs; and creating affordable housing in the areas surrounding existing public transport hubs.

TOD projects can be seen as too expensive because of their high upfront investment costs. However some cities such as Hong Kong, London, New York and Singapore partially address these by various means to fund or recover some or all of the value that public infrastructure generates for private landowner (called value capture mechanisms). There are already a number of existing mechanisms, such as development contributions, financial contributions and targeted rates, in New Zealand that could be considered to capture value from non-user beneficiaries.

What are the next steps?

A key message from the Hīkina te Kohupara report is that to achieve transport emissions reduction ambition, we will need to reduce the reliance on cars and build better communities to reduce the needs and the distance of travel. We are taking part in the Urban Growth Partnerships(external link) where many of the TOD principles would be applied, where appropriate, to inform investment decisions.

Over the last 18 months, we have learned that people behaviours can change drastically to response to life changing moments (e.g. global pandemic). What we need is to provide the right conditions to encourage the desired behaviours.

We are already seeing increasing demand for new forms of urban design and mobility options. For the 12 months to March 2021, multi-unit dwellings accounted for nearly 45 percent of all building consents issued, compared to under 30 percent only five years ago. This trend is likely to continue. At the same time, transport demand is expected to undergo a paradigm shift with the rise of ride-sharing services, micro-mobility and the adoption of e-commerce. These shifts provide very favourable conditions for implementing TOD as a way to enable more liveable communities, while at the same time, reduce reliance on cars and the associated emissions impacts.

Infrastructure investment will have long lasting effects and affect not only current but future generations. To ensure the broader intergenerational investment needs keep up with technology and societal demands, we are applying a generational approach to investment to move away from predict and provide to focus on developing a future-proofed transport system. This includes working closely with multiple agencies to achieve greater alignment across land use, urban and transport development.

References:

Centre for Transit-Oriented Development (2008), “Capturing the Value of Transit”, Prepared for United States Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration.

Ewing, R and Cervero R (2010), “Travel and the built environment: A meta analysis”, Journal of the American Planning Association, Summer 2010, Vol. 76, No. 3.

Ibraeva, Anna & Homem de Almeida Correia, Gonçalo & Silva, Cecília & Pais Antunes, António. (2020), “Transit-oriented development: A review of research achievements and challenges”, Transportation Research Part A, Volume 132, pp 110-130.

Kemp A. & Mollard, V (2013), “Value capture mechanisms to fund transport infrastructure(external link)”, Wellington, NZ Transport Agency.

McKinsey & Company (2016), “The ‘Rail plus Property’ model: Hong Kong’s successful self financing formula: What can other cities learn from Hong Kong’s approach to transit?”, June 2016.

Miguel Padeiro, Ana Louro & Nuno Marques da Costa (2019), “Transit-oriented development and gentrification: a systematic review”, Transport Reviews, 39:6, 733-754, DOI: 10.1080/01441647.2019.1649316

Thomas, R and Bertolini, L (2017), “Defining critical success factors in TOD implementation using rough set analysis”, The Journal of Transport and Land Use, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp.139-154.